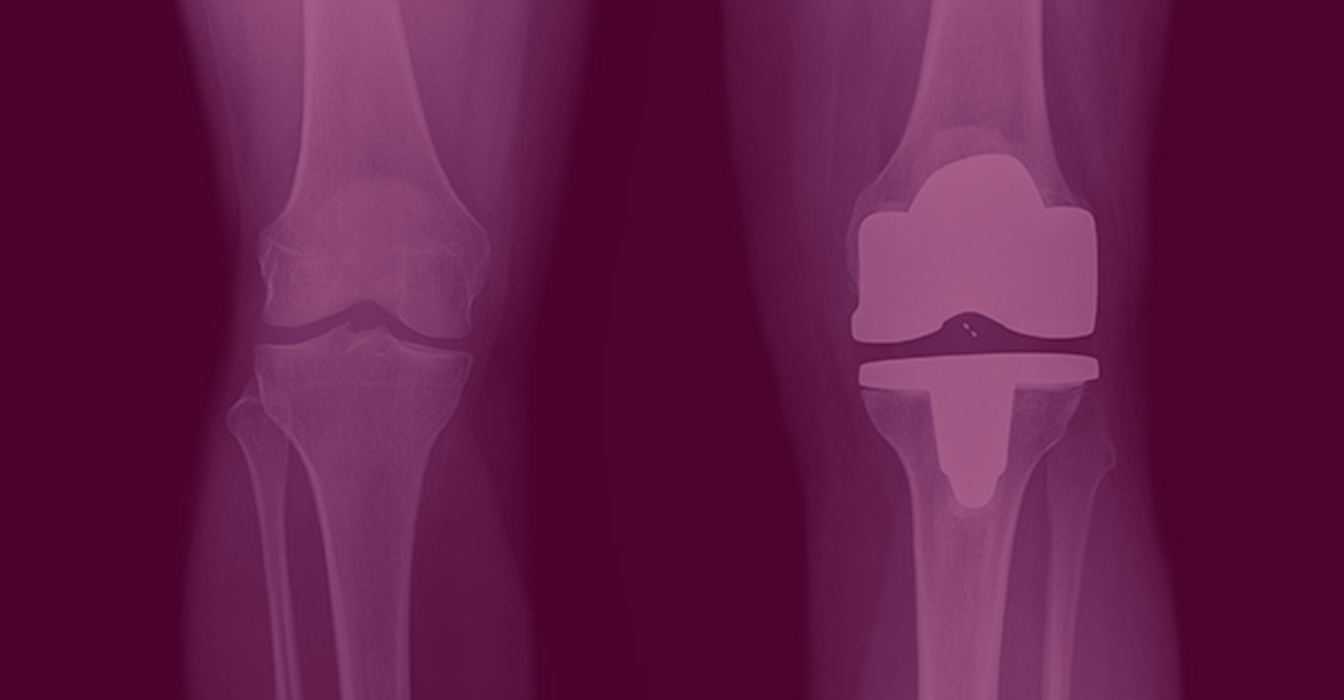

While the prevalence of osteoarthritis-related disability is greater among women than among men,i studies suggest women receive treatment such as total knee arthroplasty (TKA) later in the course of their disease.

In fact, according to a 2003 National Institute of Health Consensus and State-of-the-Science Statement, “There is clear evidence of . . . gender disparities in the provision of TKA in the United States. Although the absolute rates of TKA for men and women are similar, they do not reflect the greater burden of arthritis suffered by women.”ii The statement goes on to cite a Canadian study, which after adjusting for age, self-reports of arthritis, and willingness to accept surgery, found that women were “significantly less likely to undergo knee replacements.” i This is unfortunate, since TKA has proven to be both effective and cost-effective.

It is important to understand the reasons for the disparity to assure women receive timely treatment for their disabling arthritis. Most of the disability associated with osteoarthritis can be alleviated through TKA, and TKA can greatly improve quality of life for osteoarthritis patients.

The success of TKA in most patients is “strongly supported” by more than 20 years of follow-up data, according to the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), a database of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and related documents that is part of the Department of Health and Human Services. “There appears to be rapid and substantial improvement in the patient’s pain, functional status, and overall health-related quality of life in about 90 percent of patients,” notes the NGC.

And yet, despite the significant benefits TKA provides, and the fact that number and rate of arthroplasty has tripled for TKA surgery over the last decade,iii underuse of arthroplasty for severe arthritis is more than three times as great in women as in men.

The goal of this document is to review current understanding of gap in treatment…And what may be done to ensure women receive the most effective treatment at the optimum time.

However, anything that can interfere with this process is an obstacle – that is, fear, pain, low expectations, lack of interest, lack of understanding, patient-doctor miscommunication, financial concerns, etc. – can postpone if not totally derail treatment.

In reviewing the literature, it seems women may encounter more frequent and greater challenges in arriving at a TKA, either not getting the information they need, or acting on it in a timely fashion. Women, at least so far, are not getting the information they need, are not getting it early enough, and are not acting on it when they do get it to consider appropriate treatment options.

Elective TKA can safely be done well into the nineties; age alone should not be a limiting factor.vi As noted by Chang et al., “TKA in osteoarthritis is an important arena to investigate reasons for these differences because of the predominance of osteoarthritis in aging populations, the high prevalence of osteoarthritis among women and minorities, the potential for increased quality of life among TKA recipients and the relative cost effectiveness of TKA.

The fact is, as Robert E. Booth Jr., M.D., presented at Current Concepts in Joint Replacement,vii “Women are living longer, more athletic, more empowered for the decision-making for themselves and their families, and clearly the target population for future arthroplasties.”

Assuring those who need and would benefit from TKA have access to it is one key to the future of TKA.

Conventional wisdom holds that surgery is recommended only when discomfort turns to disability and when that disability can no longer be tolerated by the patient.vii However, studies evaluating the timing of surgery and its effect on long-term quality outcomes suggest patients should be encouraged to seek help sooner.

The facts clearly show that surgery performed later in the natural history of functional decline due to osteoarthritis of the knee results in worse post-operative functional status.vii If surgery is done too late, muscle deconditioning, loss of mobility and lack of exercise may compromise the ultimate benefit of surgery.vii Women have significantly worse preoperative functional status than men at the time of TKA,iv suggesting they are waiting longer to have surgery. And yet the single best predictor of pain and function at six months after total hip replacement or TKA is the subject’s baseline pain and function – the severity of pain and disability at the time they entered surgery. Advanced functional loss due to osteoarthritis of the knee was associated with worse outcome after six months – in other words, patients who were worse off preoperatively remained worse off post-operatively,vii suggesting that timing of surgery may be more important than previously realized and, furthermore, performing surgery earlier in the course of functional decline may be associated with better outcome.

Studies have reported that women have worse pain than men at the time of arthroplastyi and that they’ve sunk to a lower level of function before considering arthroplasty,i indicating they’re waiting longer to consider and undergo surgery.

In fact, a study of 1,120 hip osteoarthritis patients found that women were more likely to be functionally disabled and have problems with activities of daily living compared with men at the time of surgery.iii Another study found they were also more likely than men to require personal assistance in performing daily activities.

Why women wait longer to undergo surgery may be attributed to two issues that are integrally connected – that is, personal concerns about the risk and outcome of surgery, which were more important to women than men,iv and a lack of information received from their physician. Barriers, perceived or real, that are unique to women exist at the level of the interaction between the primary care provider and the patient in the process of referral to orthopaedic surgery.i As Weng and FitzGerald note, “If women tend to overestimate the risks of knee replacements and are generally less informed, they may be less inclined to undergo the procedure.

Ironically, women’s greater concerns regarding risk may prevent them from obtaining the exact information they need to address their reservations

In a focus group of people with hip or knee osteoarthritis, for instance, women were more likely to be concerned about the risks of joint replacement surgery and worsening function post-operatively. iii While men, if they ask questions at all, are interested in “devices and device technology” or in health insurance coverage.

In addition, some studies show that compared with men, women were more adverse to undertaking surgical risk and more concerned about being a burden on their families.

Health care professionals must be aware of gender differences to optimize the evaluation and care of their patients.

Even within the female gender there are differences in the concerns of white and African-American women – in one study white women were the only group to ask about drawbacks of surgery, for instance.iv Additionally, white women tended to ask process-oriented questions – about recuperation, postoperative therapy, functional recovery and limitations, and pain control – while African-American women asked about the benefits of surgery and long-term outcomes and about criteria used to for TKA and their own candidacy for it.

Mahomed et al. note that patient expectations are important independent predictors of improved functional outcomes and satisfaction after total joint replacement.viii They write that their study,viii the goal of which was to evaluate the relationship between patient expectations of total joint arthroplasty and patient-based functional outcomes six months post surgery, suggests that “patients whose expectations have been met are more satisfied with the outcomes following total joint replacement surgery.”

Health care professionals must recognize the real and perceived differences in how men and women approach their own health care, the different attitudes men and women have regarding risk and pain, and the differences between how men and women communicate with their physicians.

For instance, as Chang et al. notes, “the tendency of white men to ‘speak the same language’ as their physicians” is an important communication concept long understood by medical anthropologists in their study of doctor-patient relationships, which may contribute to men’s proportionately increased use of TKA.iv Physicians must be sensitive to language and communication issues to optimize their evaluation and treatment of females with osteoarthritis.

Copyright 2026 Design & Developed by Midnight Digital Pvt.Ltd